FALL 2019 3-week term

When I was young, the first house I remember living in had a single big tree in the driveway. We had a long driveway leading up to our little trailer home, and you passed by that big tree right before you parked. When I was four, a tornado hit late one night and tore up that tree from its roots, almost like it had never even been there. Little did I know at the time, but this was foreshadowing for how I would never form roots in one place.

Purple was my favorite color at that age, and so it was the color my mom painted my bedroom. The color was my signature. Every time I wrote my name it was in that color. I had a stuffed purple hippopotamus that I could not sleep without, and it even was the color of the cast on my arm as I started kindergarten. Purple was my favorite color before I knew it was the hue produced when my father laid his hands on my mother and then on me. The very first memory I can recall was of my father leaving the little trailer we called home for the babysitter. I did not understand what was going on or why, and yet despite the purple pigmentation that surrounded my mother’s eye and my own tiny body, I cried. I remember running after my dad, even as my mother screamed at me to come back. “Can I come with you?” I sobbed, grabbing onto his briefcase. “No, but I will see you soon” he replied. “What’s going to happen to us daddy? Please don’t go, please.” I begged. He did not reply, but instead removed my hand and walked to his car, leaving us and his home behind. I did not understand then why it was so easy to leave, but throughout the years I began to have a better grasp on the concept of home, and a better understanding of why it was so easy for him to leave. The night my dad left, the Texas sky was purple. I hated that color until I fixated on another color to hate, red.

Red. Red was all I saw through my bright blue eyes after my dad left. I was angry at my mom, my sister, my dad, and at the world. I was most angry with myself, though, for not doing what I could to keep our home and our family together. My picture-perfect idea of a family and my purple room was no more, all in one fell swoop. Instead, at five years old, I was walking up the stairs of a tan brick building, into a tan two-bedroom, two-bath apartment. Everything was that yellowish brown color- the walls, the carpet, the furniture. This new place that I was supposed to call home was only “temporary,” yet it did not feel temporary, nor did it feel like home. It stayed “home” however, until that October. That Halloween I dressed up as Jesse from Toy Story. I had a bright red cowboy hat on with matching red cowboy boots. As I sat on the couch in our living room and kicked the monogrammed spider Halloween bucket my mom always made me carry, I looked up excitedly when I heard a knock. It was my dad’s year for Halloween and he was taking us trick or treating in my grandparents neighborhood. “Wait here.” my mom sternly said, and I sat back down with a huff. As I began to grow antsy and banter back and forth with my younger sister, our voices began to raise. However, I began to notice our voices were not the only ones that were raising. As I peered down the hallway in that apartment, I never realized before how long it was until then. As I watched horrified, my dad and my mom’s new boyfriend got into each other’s faces, screaming. The next thing I knew, my mom was racing down the hallway and my sister was screaming. As I watched, one of them slammed the other into the wall and fists began go fly. The last thing I saw before my mom pushed me and my sister into her room and slammed the door, was red. “Daddy’s bleeding, daddy’s bleeding!” I screamed. “He’s gonna kill him, he’s going to kill him!” my little sister wailed as we heard the beating continue outside. To this day, I still cannot say who she thought was going to kill who. That day, the color red and Halloween were put into my subconscious book of things I hated the most. And once again, I did not understand what was going on or why, but as my mom dialed 911, I already knew that we would be permanently leaving that place that we had only temporarily called home.

Blue was my favorite color in high school. Blue was the color of my room at the time; it was the color of my volleyball uniform, as well as the color of my first boyfriend’s eyes. Blue was also the color I saw every time I cried and looked in the mirror because I was lost. I had lost myself throughout the years of losing those brick and mortars I called home. I was labeled a loud girl with daddy issues and in some ways, I justified that label by saying the things most would not say and doing the things normal Christian girls should not. I did this because I knew I would never call where I was home because I would never be there long enough. Despite this, however, my first realization of what home actually is was during this time. I did not understand at the time what was happening, just that I had reconnected with an old friend as I started out at a new school for my junior year. We spent every day together and she drove me home from school. She was my only friend that was allowed to spend the night at my house and the only friend that knew me better than I knew myself. Lexy knew everything about me as well as my family. She became a part of my family, so much so that she went on vacations with us and babysat my siblings when I was not around. At the end of my junior year, I once again was transferring to another school. On my last day there I cried, not because I was having to move and leave another place, but because I was having to leave her. I had moved and left close friends before, but this time it was different. I remember her hugging me as we sat on the curb by the baseball entrance gate, and her telling me it was going to be okay. She told that I would like my new school and that we would still see each other all the time. Then she said something to me that would forever change how I look at things and people. “We are going to become distant and not be as close anymore,” I cried to my best friend. She laughed and pushed my arm off my knee and said, “Bitch, we’re practically sisters, you’ve always got a home with me.” That is when I realized that home is not a place; it’s a person. And for the first time, I understood that I did not need a house with a white picket fence and a perfect family, but rather the right kind of people that I could call home. Blue is still my favorite color to this day, and Lexy is still someone I call home.

Time and memories seem to blur together when we are young. Some things stand out to us when we recall certain ages, like winning our first trophy at age seven or getting that big Christmas present we asked for from Santa at age ten. I do have those moments that I hold close to my heart, but the one thing that overshadows those moments for me is how after I got my first soccer trophy at age seven, I moved schools and had to change teams. I was not at a school long enough to make close friends that I could show the amazing Christmas present Santa got me. I never event spent more than one Christmas in the same place until the seventh grade, but I never knew any different, so it did not bother me. I did not really question what home was until I came to college. Home has always been a complicated and uncomfortable subject for me until now. When I am asked, “Where are you from?”, I proudly say “Fort Worth, Texas!”, because it is true that I am from there. I have never lived anywhere else until I moved to college. But if there is a slight change in wording and I am asked, “Where do you live?”, I will proceed to say “Virginia” because it is where I live now. I do not go “home” to Texas much because of my family. I have found it to be healthier to call my home elsewhere. We are taught from a young age the idea of what home is. We are taught your home is what defines you and shapes you into who you are and who you will become. Not having a physical place to call home calls into question for me what home actually is, and I find my answer is quite different than most. I have never had roots anywhere until I came to Virginia, and even my roots here are quite complex. My roots are not fixed into solid ground like you would expect a tree’s roots to be, because my roots are the people around me, and they are every moving and every changing. Maybe it is because of my childhood and the daddy issues I have so easily been branded by in the past, but I find that the best kind of home is made up of those closest to me. There are several more people in my life that I now I call home, and I like to think that my roots are far deeper than those of a tree that can be torn down by a tornado.

Sep 13th, 2019 by Sara-Jane

That man seems to me to be equal to the gods

who is sitting opposite you

and hears you nearby

speaking sweetly

and laughing delightfully, which indeed

makes my heart flutter in my breast;

for when I look at you even for a short time,

it is no longer possible for me to speak

but it is as if my tongue is broken

and immediately a subtle fire has run over my skin,

I cannot see anything with my eyes,

and my ears are buzzing

a cold sweat comes over me, trembling

seizes me all over, I am paler

than grass, and I seem nearly

to have died. — Sappho 31

My mother always told me that staring is impolite. As a child, I was always reprimanded for staring at others for too long. The ladies in the shops and cafes would see me and at first, they would smile and wave a normal reaction to a small child looking at you with such attention. Eventually, my intense gaze would become too much, and those I chose to set within my line of sight would start to squirm, the effects of being observed overwhelming them. At this point, my mother would grab my hand in a tight grip and force me to apologize.

Tonight there is no one to stop me from staring, out on my own I can do as I wish and my wish is to stare at her. Her hair is just long enough to kiss her shoulders, cascades of curls and flames that she cards her fingers through without getting burned. The man beside her must have made a joke because her face is sudden skyward, her neck curving back, long and beautiful, as her whole body shakes with laughter. My heart jumps into my throat. If I were a braver woman I’d approach her. Sit beside her perhaps just too close so our thighs touch ever so slightly. I’d lift my hand and tangle my fingers in those flames framing her face, my hand coming away charred and black from touching something to pure and hot without thinking. But it’d be worth it.

So caught in my fantasy I did catch her looking back at me until it was too late. Our eyes met, amber eyes scanning me up and down with a hint of amusement. Delicate fingers waved at me. I felt dizzy, my face no doubt hot and flushed as I quickly turned in my chair to face the other side of the room. I down the last of my drink and closed my eyes, overwhelmed by everything I saw now.

“You don’t have to be jealous.” a low voice danced into my ear, the owner close enough I could feel her breath against my kneck. “I’m not their type after all. At least not for this crowd.” white teeth poke out from behind red lips when she smiles. The seat next to me is open so she claims it as her own. Freckles are sprinkled across her nose and cheeks, a small detail I couldn’t see when she was sitting so far from me but now this close I can count every mark along her skin. There’s even a small scar above her lip hidden well behind the red.

My tongue has turned to lead in my mouth, but she has that look in her eyes like she’s waiting for me to speak. To say something and keep her interest. I don’t want her to leave, don’t want her to think me weirder than she already does so I open my mouth and pray anything will come out.

“I’m sorry.”

“Sorry? For what?”

“For staring, it was incredibly rude. I’m sorry if it made you uncomfortable.”

Hair spills from behind her ear and shields her face from my view. Unable to read her expression any longer my breath catches in my throat. Her nails are painted the same shade as her lips I notice when she tucks the hair back behind her ear.

“Not uncomfortable, flattered is more like it.” The air stuck in my throat comes loose as a cough, my face heats again. “I’m Amy. Let me buy you a drink.”

The bartender stops and fills our glasses giving me a chance to breathe normally again. We must be a weird sight to him, the bar partons are all men except for us and another woman who left some time ago. Perhaps she came in looking for something and quickly realized she would not be able to get it here. No one can blame her for coming in and trying, the fact that this is a gay bar is not well advertised to the general public.

“Shelly.” I introduce myself finally and wrap my hands around my glass, grounding myself in the moment.

“Nice to meet you.” Amy winks and raises her glass towards me expectedly. Hesitantly, I raise my own and our glasses clink together. The rest of the night passes us by and Amy somehow eases me out of my shell. Before long we’re talking and laughing together as our bodies subconsciously inching closer and closer with each passing hour.

Closer to midnight, I’m drunker than I had planned to be and with that comes bravery. My hand drifts through the air before I know what I’m doing and my fingers tangle themselves in firer locks and come away without a burn.

Sep 13th, 2019 by felton21

A large black dog peels away from the shadows and into the path between tombs, the heavy rain passing through it as easily as it does the air. It’s silent in its patrol despite its mass and doesn’t stir a puddle as it trails toward the church on the edge of the graveyard, appearing more like the shadows it came from than a dog. In fact, one could mistake it for a wolf if they weren’t able to make out the thick, red collar circling its neck. Even then the distinction between dog and wolf would be nearly impossible to make.

The decaying church the dog makes its way to can hardly be called a church anymore. Only two of the four outer walls remain standing and most of the inside has been washed away in Betsy, then buried by Katrina. All that fully remains of the once remarkable structure are the few pews that were trapped in the basement when it flooded, faint imprints of what was the preacher’s stand, bits of tattered cloth that once served as wall covers, and a few of the newer additions that were bolted to the floor when the church was renovated in the thirties. If there weren’t a sign marking the historical landmark, one may believe there wasn’t a church here at all. Nevertheless, the ground is still consecrated and Grim still has its job.

The Grim sniffs the air once it reaches the closest wall, ensuring its solitude in the deepest part of the Yard. After a moment, it forges deeper into the unstable structure and rises onto its hind legs, shifting and shrinking from its impressive nine-foot standing height to a reasonable six foot two inches. Its thick, black fur changes to a long, black fur coat over a black button-down shirt and pants. In under a minute, the Church Grim is gone and Shiv stands in its place, shaking his head to clear the hair from his eyes. He glances around once more for any passersby then slips back out into the Yard, tugging the knee length coat around his shoulder as he plunges into the torrent.

Sep 13th, 2019 by lamphiermeier21

August 26, 2005

Thank God it’s Friday! School just started and I’m already over it. We’re learning about Shakespearean tragedies in English and it is so dull I cannot focus. Even if I wanted to pay attention in there I couldn’t, because John and Andre sit behind me and they always fool around, touching my hair and bothering me. They may be my best friends but I am so happy I don’t have to deal with them in any of my other classes. I’m taking Trig with the upperclassman since I did so well last year and tested out of the prereqs. It’s great for my future, but now everyone thinks I’m some math freak. This, in addition to being one of the only out lesbians ,really set me up for success. Freshman year is supposed to be my year so hopefully things start looking up. Mamma told me I just need to get involved and find something I like to do besides hanging out with my girlfriend. She suggested I try out for the play like she did back in the day. Honestly, Mamma seems more excited about it than I am, but at least I’ll get to wear a cute costume and maybe make more friends than Andre, John and Julie. Either way, this weekend is going to pass too quick, and I am not excited to re-enter the doors of Alfred Lawless High on Monday.

After school today I went over to Julie’s house and her dad was watching the news before he went to work. The governor issued a state of emergency because of the weather. It seems there is a big storm coming this way. I always get nervous whenever there’s bad weather. He said it’s probably just going to pass and that I shouldn’t worry so much. I wonder what Mamma thinks about it. It’s almost ten o’clock, so she should be home soon.

XO,

Celina

August 27, 2005

I woke up this morning and did my homework. I only had a few assignments, but I want to get them done so I didn’t have to think about them anymore. Mamma had the day off, so she sat in the armchair next to me and ate her cereal while I worked. I asked her if she was worried about the storm coming. She said it wasn’t anything we couldn’t handle. We sat in silence for a long time. After a while, she sighed and got up. As she passed behind my chair to leave, she gave my shoulder a light squeeze. I have a small bag packed just in case.

Julie came over at noon. Her dad got stuck at the nursing home and had to work a double shift. She hates being alone for too long, so every time her dad works extra hours she winds up at my house. We live two blocks away from each other on Jourdan Ave., so it’s really easy for us to spend time together, much to my mother’s annoyance. Mamma supports Julie and I, but she thinks we spend an unhealthy amount of time together. What does she know? The good thing about Mamma though is that no matter how she feels, she is always polite to Julie and makes her feel welcome.

When she got here, she told us that Andre’s family left last night. His mamma had such a bad feeling about the storm, she made them pack up in their van. I guess they’re going to visit his aunt in Shreveport. I was surprised to hear they left. Andre’s mom is always talking about how she survived Betsy. It’s not just Andre’s family leaving though. A voluntary evacuation is happening in the city. I asked Julie if her and her dad would leave. She laughed and said, “Now how would we afford something like that!” I’m glad she’s so calm about it.

Julie decided to sleep on my couch tonight.

Sep 13th, 2019 by kamal20

Dear Dhaka,

As I am writing this letter, I am thinking about you. It has been years since I last saw you. Are you still the way I left you? You change so fast, a little too fast. I don’t know what to expect from you anymore. Are your sky still a little grey and the buildings too tall? Are your streets still overcrowded? Do you still smell like home?

Dear Dhaka,

I think about you often. I think about the smell of beef bhuna being cooked in Rashfee’s apartment making its way into my room; the strong smell of cardamom that she put a little too much of. The sound of Priti’s music and her sa re ga mas coming from the 2nd floor. I think about my afternoon walks to the Dhanmondi lake, when the sky is still grey and the air smells like wet grass. I think about my walk down the narrow lanes of road 7 and seeing masala cha, brain bhaji, and fuchhka carts. I think about the tamarind mixed with green chilies coating the lentil doughs, the spices making my eyes tear up, and how I still can’t have enough of it.

Dear Dhaka,

Dear Dhaka,

Do you still have people coming out on the streets chanting Joy Bangla when we defeat India by 3 wickets? Do you still have red and green floating across the crowd and playing the songs from [19]71? Do you still stop the cars on the roads and just let people dance to this victory? I think about those people. I think about cricket. I think about how much this victory means to us. And not just because getting that trophy means the world knows about us, but it means the world sees us. The world sees our trauma and fight. The world sees that this game is not just in the field, but also on the borders. Their cricket bat is not just hitting our ball, but also our 13 yr old girls playing tag near the border, and forgetting for just a brief second that they were not supposed to cross that white line. We do not just run to score, we run from their bullets. This cheer is not only about the tears we shed for our win, but for all the blood of we shed because of them. I think about it a lot. I don’t like thinking about it at all.

Dear Dhaka,

I think about you — about your trees with brown leaves and colorful roses. I think about the potholes on the roads and bridges with blue lights. I think about your five-star hotels, and ripped tents by the dumpsters in Mirpur 7. I think about the tall buildings with seven pools on the rooftop, and the Mayor’s son stoning the stray cat. Do you still let young Fatima clean shoes? Do you still let her father come home drunk and beat her mother? Do you still smell like home?

on the roads and bridges with blue lights. I think about your five-star hotels, and ripped tents by the dumpsters in Mirpur 7. I think about the tall buildings with seven pools on the rooftop, and the Mayor’s son stoning the stray cat. Do you still let young Fatima clean shoes? Do you still let her father come home drunk and beat her mother? Do you still smell like home?

Dear Dhaka,

I think about Tonu. Why did you hate her so much? What did she do to be raped, murdered and be thrown out on the bushes left to rot? You never punished the man who did this to her. Why is he so important to you? Why is he not rotting away? Even after we set fire for her, even after we blocked your streets in her name, and even after all the women in the city cried for justice — did you still not care? Did you hate her that much?

Dear Dhaka,

I spent 19yrs of my life with you. You gave me a lot to cherish. You gave me a lot to hate. I appreciate your rain, and but I resent your flood. I do not like your grey sky, but the thunders are not scary. I cannot tolerate your jammed packed roads, but I cannot sleep without the noise. I hate your dry air but without it, I cannot breathe. You are too loud sometimes, but I don’t mind speaking a little louder. I think about Kalam uncle’s dudh cha beside my school, and all the conversations that unfolded over a cup of tea there. But why did just let his son whistle at me, every time he saw me? Why did you not stop him from staring at my ankles and touching my waist?

waist?

I think about you. I enjoy the privilege of having a place I can call home. But I am not sorry that I left you. Yet here I am today, 9000 miles away from you, and I still think about you.

Yours truly,

Tanna.

Sep 13th, 2019 by Rachel

Ode to Angela, who works at Brookside.

If I were to see you in public,

I would have to duck out of your sight.

You wouldn’t recognize me, of course,

wearing clothes other than my pajamas

and without raccoon eyes of old makeup.

At night, you’re my closest friend, my confidant,

behind the counter of the old gas station.

Always good to see you, you tell me.

Likewise, I say, forcing a smile.

Tonight your hair is pink. Tomorrow? Who knows.

You notice I’m crying before I do.

She was a real sweet lady, you say,

Your grief as genuine as my own.

My total is three ninety-nine.

You didn’t charge me for the slushee.

Ode to Nicholas, a childhood friend

I gave you some flowers for your vase.

They brightened up your room,

but they were never meant to last forever.

We tried to talk about our futures,

but were too scared to get very far.

The next time I was at your place, so were they,

looking comfortable in their spot on your desk,

some petals lost, but beautiful as ever.

That was the day of graduation,

when we had our first big fight.

I came over again. The flowers remained.

They were covered in brown spots, and wilting.

I can’t get rid of them, you said. They’re from you.

I told you I was leaving town soon.

You had never looked so betrayed.

I visited you when I was back home.

The flowers were rotting, almost black.

I still want them. They were beautiful once.

You tell me what’s new, but I can’t listen.

I am too distracted by the flowers’ stink.

I don’t go to your place anymore.

You said you didn’t want to see me,

and I was flooded with guilty relief.

You finally threw the flowers away.

I almost wish I hadn’t gone with them.

Sep 12th, 2019 by alexander21

Throughout my twenty-two years of life, I have lived in a myriad of houses across multiple states. I was born in a small town in Texas thirty-five miles from any city of importance and lived there for roughly the first three years of my life; between then and my tenth birthday my mother and I moved to North Carolina, back to Texas, back to North Carolina with a half-brother and step-father in tow, then Florida, and for the third and final time, back to North Carolina. I celebrated my tenth birthday one week after moving, friendless and in a house that was not mine.

Sep 12th, 2019 by potter20

Bellocq’s Ophelia was a beautiful yet grim portrayal of the life of a sex worker. There are many preconceived notions of sex workers in society, and I believe many of these notions are through the eyes of men that have been passed. Throughout the poems in Bellocq’s Ophelia, we see how Ophelia is constantly objectified. She is objectified by her profession and her body, including her skin tone. Two such lines that really struck me was in Countess P-‘s Advice for New Girls, “For our customers you must learn to be watched. Empty your thoughts- think, if you do, only of your swelling purse,” and then, “Think of yourself as molten glass- expand and quiver beneath the weight of his breath.” These two lines show how a sex worker should not think and how, when working, they are to be supple to a man and his wants and desires. Bellocq’s Ophelia is written through the eyes of Ophelia and her observations, yet, what is ironic, is the fact that the book is observing her through these pictures that capture the beauty of her and her life. We observe the objectification she is put through and how being a sex worker affects her. We see how the profession of a sex worker is not always black and white like we may have thought. So often when we hear sex worker and then are shown a picture, that is all that is able to be seen. However, in Bellocq’s Ophelia, we are able to see without hearing sex worker and that is what makes it beautiful.

Sep 12th, 2019 by carriveau21

Nahomi and I on the front steps of my house on Halloween 2004.

Nahomi*, my next-door neighbor and first friend, was Hispanic. We went to the same elementary, middle, and high school, but she was a year older than me. Growing up next to Nahomi was so much fun and taught me a lot about the Mexican culture, giving me a world view from my own back yard. We were the best of friends from an extremely early age, I cannot remember a time when we were not friends. A lot of my first memories from childhood include her. During the summer we would spend almost every day together, whether it was at her house or mine. Some of my most fond memories include trips to the school playground down the street from our house and bike rides around our neighborhood with her sisters Silvia* and Marcy* who were about nine and five years older than me.

On days when we got tired of the park, we would sometimes help my mom in the garden. If the ice cream truck or paleta cart passed by, my mom would buy us ice cream as a reward. Mobile food vendors, whether walking or driving, were a centerpiece of our childhood. Living in a primarily Hispanic neighborhood, mobile food options were not just limited to Ice cream. The truck would also sell elote, a Mexican street corn dish with mayonnaise, cotija cheese, and chili powder. This was one of Nahomi’s favorite foods, I, on the other hand, hated it, but she made me try it almost every time she got it. I was more partial to the chicharrones de harina, with lime and sometimes a little bit of Valentina, a Mexican hot sauce and staple that can go an almost anything. Nahomi and I would split the huge bag, but new would never finish it. We would, almost always, eat them outside on the front steps of one of our houses. The mango and snow cone man was another hot commodity, also enjoyed on the front steps.

We were constantly introducing each other to new things like foods, drinks, and TV shows. It was mostly Nahomi introducing things to me, but I introduced her to root beer, baked mostaccioli, cantaloupe, and some shows on the Disney Channel. Nahomi showed me a ton of Mexican pastries and candies, that I could get at one of the several Hispanic grocery stores in town. Sponch galletas and paleta payaos are still some of my favorite treats. She introduced me to her mom’s homemade flautas, mole, pozole and still to this day, the best sope I have ever had. Nahomi and her other sisters also figured out how to put the English subtitles on their TV, so I could watch Rebelde with them and still understand what was going on.

Most of the time I was at their house, all the girls would try to teach me more Spanish, which I was super excited to learn. I always felt left out on the playground not knowing what most of the kids were saying. Nahomi’s Mom didn’t know a lot of English, so if it was short enough, instead of directly translating what I was saying to her, they would tell me what I wanted to say in Spanish and then I would speak to her like that. The other way they would try to teach me was, if I had to ask for anything, I would have to ask in Spanish, or at least try to ask. Again, if I did not know the word I needed, they would tell me. They would also make sure that I spoke with the correct accent as to not sound like a “gringa.” This came as a great skill to have acquired at an early age. By the time I had to take Spanish in high school, I had perfected the proper Hispanic vernacular, and in doing so, I got A’s on all of my Spanish speaking assessments.

I felt like I was a part of their family. I was invited to a bunch of family parties, and as we got older, I was jokingly pinned “the token weta.” Before every party they would have, it was a full sibling effort to try to teach me how to dance the Bachata. Silvia would bring a boom box outside and Marcy and Nahomi would try to teach me the steps in the driveway. The learning process took years, and I still do not think I do it right, but I am a lot better than I used to be. Her family taught me how to celebrate birthdays the right way. It wasn’t a real party until everyone was screaming “Mordida! Mordida!” and your face was shoved in the tres leches. The lively celebrations would go on till the early morning, sometimes till 3am, but I normally had to leave before 10pm.

Her older sisters, especially Silvia, from my own perception, looked up to my parents. When Silvia was in 3rd grade, she came over to our house and asked my mom how she could convince her own mother to let her take English 4th grade instead of bilingual 4th grade. Together, they were able to produce a plan, and the following school year, Silvia flourished in the 4th-grade English class. When my mom was PTO president of Prairie elementary, she sometimes would have to write the handout fliers for school events, but they needed to be in English and Spanish. So, she would frequently pop over to Nahomi’s house and ask one of the older girls if they could translate the handout flyer for her. A few years later, Silvia would come to confide in my parents and ask them if they would be willing to write a character letter for her DACA application. I was not entirely unaware of the presence of undocumented people in my community. Growing up with friends whose parents are undocumented gave me a better understanding of the immigration problem. A young child should never have to ask their parents if her best friend can live with them if her parents get deported. Knowing my entire community could change and the parents of my closest and oldest friends could have their entire lives torn apart, makes me have a different opinion than others on the solution to the immigration issue.

There were so many Mexican restaurants in our town, but my mom was afraid to go into some of them because she did not know Spanish, so she was unsure if she would be able to order. This came up in conversation one time when Silvia and Nahomi were over at our house. Over the next few weeks, Silvia, Marcy, Nahomi, my mom, and I would go to their favorite restaurants in town, the ones they thought were the most authentic and best tasting. They would recommend what dishes we should try and most importantly, assist us in placing our order. Eventually, I improved enough to be able to mostly order on my own, but it was not until high school that I was confident enough to go to the restaurants they took us too alone. Even though I do not think I will ever return to my hometown to settle down, I will always look forward to going back home, especially for the food. I can get tacos and tortas just down the street from my house that are better than any restaurant around here. Come to think of it, the Mexican food item of the day that was served in my high school cafeteria was better than anything at I have ever eaten at El Mariachi or La Carreta, and I have yet to find a place that even sells chicharrones de harina in Virginia.

*Names have been changed to help protect identity

A paleta man and his paltea cart

Elote

chicharrones de harina

Valentina

Paleta Payaso

Sponch Gelletas

Sep 12th, 2019 by Sara-Jane

While The Moviegoer was very hard and time-consuming for me to get through, I did find myself relating to Binx. When reading novels with neurodivergent main characters I often find myself trying to diagnose them with personality disorders. This probably comes from my own struggle with my disorder and my need to find things, people, or characters that make me feel normal. While I do not believe Binx and I share the same diagnosis there are many symptoms that I can relate to.

For one, his disdain for the mundane life cycle. The cycle of waking up, eating breakfast, going to work, and coming home is not as stimulating for some as it is for others. While the routine of this can help move a person to recovery and normal life the need for stimulant controls people like Binx and I. We’re always looking for something new, something different that can keep us moving because settling into something we know can cause a bad light to cover everything we look at.

The other thing is his relationships with his secretaries. While I have never had a secretary to have an affair with I do have the deep need to connect with someone on a certain level. Binx starts relationships with these women thinking that he’ll find what he needs and when he doesn’t he lets the relationship sour and end even if he doesn’t notice that it’s him causing it. He says that by the end of the relationship it’s almost a relief to let it fo since both parties can not stand to be around each other. Interpersonal relationships are something a lot of people with a personality disorder struggle with. While I do not like to admit it, I will hop from one relationship (usually platonic) to another in search of something to stimulate me and make me feel whole. If the relationship doesn’t give that to me I’m usually the first to let it go and forget about it immediately.

While I may not have enjoyed the journey of this book, I was rather impressed with the author’s ability to show such a complex character.

Sep 11th, 2019 by bell20

Sep 10th, 2019 by Rachel

To Angela, Who Works at Brookside

If I were to see you in public,

I would have to duck out of your sight.

You wouldn’t recognize me, of course,

Wearing clothes other than my pajamas

And without raccoon eyes of old makeup.

At night, you’re my closest friend, my confidant,

Behind the counter of the old gas station.

Always good to see you, you tell me.

Likewise, I say, forcing a smile.

Tonight, your hair is pink. Tomorrow? Who knows.

You notice I’m crying before I do.

She was a real sweet lady, you say,

Your grief as genuine as my own.

My total is three ninety-nine.

You haven’t charged me for the slushee.

Sep 10th, 2019 by alexander21

abandonedplaygrounds.com

Located on the corner of a lively intersection in Forest, Virginia is a little green house. Compared to the vibrant houses that surround it on both Thomas Jefferson and Waterlick Road, this house is quite bleak; however, there is something peculiar about it. Despite the plywood boarding the two windows to the left of the porch suggesting that onlookers keep out, there is something inviting in the front of the house. Perhaps it is the white awning perched before the front porch; the pale green siding of the house, fading ever so slightly as each year passes; or the forgotten window to the right, beckoning those who are curious to peek inside. Continue Reading »

Sep 9th, 2019 by weasley7345

The Diary of a Storyville Sex Worker

Storyville was the red-light district of New Orleans, Louisiana, from 1897 to 1917. It was established by municipal ordinance under the New Orleans City Council, to regulate prostitution and drugs. Prostitution became a lucrative source of income for the city. At the peak of its success, there were approximately two thousand prostitutes and forty brothels, with New Orleans’ sex trade totaling $15 million per year.

After twenty years of operation, the U.S. Army and Navy demanded that Storyville be closed, considering the district as a ‘bad influence’ on the sailors at the nearby Naval base. The District was closed by federal order on October 10, 1917, despite the strong objections of the New Orleans city government and Mayor Martin Behrman, who proclaimed ‘You can make prostitution illegal, but you can’t make it unpopular” (Storyvilledistrictnola.com).

The following are diary entries from a prostitute in Storyville, Louisiana, written between 1915 to 1916, some of the dates are not clear due to age and deterioration, there is also missing pages. The book was, amazingly discovered, approximately 90 years later, during the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina which devastated New Orleans in 2005.

During Katrina, levees broke flooding much of New Orleans. The force of the water literally raised the dead from their resting places. Nearly 1000 coffins and vaults floated along the streets of the Gulf Coast. Many of the coffins lacked identification, so it became necessary to open them to identify the remains. It was then that the diary of Cora May Johnson, a Storyville sex worker, was discovered. Birth records indicate that Ms. Johnson, was born in Boone, North Carolina on February 10, 1896, and that she was born to a negro mother, her father, an unknown male, was listed as white. She was seventeen when she went to work as a prostitute in Storyville. Her diary gives some insight into the lives of Storyville sex workers.

January 15, 1915

Mr. Rivers, a regular client here on Basin Street, came to visit today. He is a gentle and kind man, with an almost shy quietness about himself. He is a handsome man of athletic build with dark, wavy hair, a man that could have any woman of his choosing. His hands are as soft as rose petals, and his crystal blue eyes are as deep as the ocean. He appears to be well-bred, highly educated, and always acts as a gentleman to the women here. I seem to be a favorite of his since his first request is to spend his time with me, and he often schedules appointments in advance to ensure my availability. He is, as well, a favorite of mine.

He frequently asks me to read poetry to him on his visits. Today it was a poem by Eloise Bibb.

Judith

“O Juda! if thou wast endowed with power,

Thou would’st describe that grand and solemn hour.

In yonder sacred oratory there.

Thou dost behold a woman strangely fair,

With classic brow and jet-like dreamy eyes,

Whose liquid depth out rivalled Italy’s skies;

And penciled brows ‘neath glossy, raven hair,

Adorned the lids with silken fringes fair.

Though haircloth clothed that form of matchless grace,

It could not hide the beauty of that face.”

I do not understand it entirely, but it is about a woman who prays for her people to be set free, her prayers answered. The words are beautiful, and they bring tears to my eyes as I read them.

Mr. Rivers gifted me this journal. He says because I feel the magnificence and beauty of poetry that I should try writing. He inquires about my educational background, and I, ashamed, bow my head down to tell him how I attended a one room negro school, in a small town in the Blue Ridge Mountains of western North Carolina. It was in the same building we used for church on Sundays. I told him how the building was desperately in need of repairs, but those few negros that were fortunate enough to attend did not complain. I go on to say that I learned arithmetic, reading, writing, history, and geography from a teacher provided by the American Missionary Association. I inform him that I went as far as I could go in that schoolhouse and once dreamed of attending Spelman College in Atlanta, Georgia. He smiles, wipes a tear from my eye with his handkerchief and tells me to hold fast to my dreams.

January 18,1915

{illegible entry}

January 22, 1915

It is unusually cold today here on Basin Street. I wish for snow. Snow reminds me of my childhood and my dear mother. She would make snow cream for us after we finished our chores. The fresh cream and sugar mixed with the cold snow was a treat. Mother would tell us not to eat it fast for it would make our heads hurt from the cold. I tried to listen, but it tasted so good it was hard to eat slowly. My sister would savor hers and be the last to finish as we sat there waiting, hoping she would share. She didn’t.

I know Mother feels very bad about sending me here to work although, she did let me decide in the end. She would have come herself except her bent and broken body from all her years of work would not earn much pay here. I thought I would be able to save some money for my education, but it is hard for women, especially whores, since we cannot leave the district. I send Mother most of my earnings to help feed and clothe my brother and two sisters, all younger than me. They all have the same octoroon father who was a sharecropper until he died working in the field. My father, a white man, used to come by when I was a child and bring me candy, but I have not seen him for years. My mother foolishly loved this man and fell prey to his charms and fabrications of their future. I don’t think of him much, but I miss my momma and my brother and sisters.

January 31, 1915

Mr. Grimes, the good mayor himself, came to visit today. I detest his visits. He is fat and sweats a lot. He grunts like a pig when he is on top of me. The good part is he does his business rather quickly and leaves me a five-dollar gold piece on the bureau as he closes the door behind him. He never talks except to say what delicate white skin I have for a negro. I must hold myself back from saying thank you Mr. Pig; instead, I give him a polite smile.

February 1, 1915

A new girl came to live in the house today. She looks so young. Did I look that young when I first arrived? I have been here for two years now. I remember the day I walked in the front door. I never imagined a whore house could be so fancy! Velvet curtains and chairs. Chandeliers that sparkle like diamonds, reflected by the mirrors that are everywhere. The sculptures and paintings, all done by local negroes, are breathtaking. I am envious of their talents, but I also mourn for their struggles. It seems to me that such capability is wasted by not being publicly displayed.

I will wait and meet the new girl at this afternoon’s tea.

February 10, 1915

Today is my birthday, and I once again think of mother. As far back as I can remember, mother always managed to find enough money for material for a new dress for me on my birthday, a simple cotton print, sewn together by her hands and made with love. She would make a cake as well. Sometimes it was a large cake, enough that everyone could have a piece but when money was scarce it would be small, more like a hoecake, enough for one, but I would still share a bite with Mother and one each for my siblings.

As I look in the mirror, I momentarily feel beautiful and ladylike, my long dark hair, with its natural curl, down and framing my face. I notice the curve of my hips, and the fullness of my breast, the length of my legs and the golden color of my eyes. I wonder if Mother would be ashamed of me now in the silk gowns, I wear each night, with my breast half exposed, pushed up with tight corsets, to entertain and entice the men who visit? Would she frown at the powder on my face I use to make my skin whiter? The rouge on my cheeks to make me look as though I were blushing with innocence? The red lip color applied to fuel lust? Would she hate, that here, because of my eyes, they call me Amber instead of the name she gave me at my birth?

I sometimes imagine myself as a stage actor, dressing and playing the part of a charming lady, out on the town, laughing at his jokes, quietly listening to his tales of work and woe. Then I return to reality, and I am but a whore. When I lay with these men, strangers really, I become inhuman, a piece of furniture, a tree in the woods, a statue. It is the only way to endure my work, along with knowing why I am here: my mother, my sisters, and brother. Removing myself makes it tolerable. My work is easier on the body than working the fields, but it is harder on the heart and soul.

When there is a new girl, as there was tonight, the men become foolish rival suitors trying to charm her and win her attention. The winner will always be the man with the most cash in his pocket. Her name is Nellie; she is from Mississippi. She is young, tall, and slender, with small breast. Three men were especially enchanted by Nellie, including Mr. Grimes. I prayed that her first time would not be with that pig! I had been chosen by the police captain when I saw her head up the stairway with the drugstore owner, Mr. Percy. She was in good enough hands.

My company for the night, Captain Morgan, is a strange man. His request is always the same; to have me undress slowly and then lie on the bed while he pleasures himself. He then sits in the chair, smokes a cigar and leaves, dropping a few coins on the bureau. I have earned my pay for the day.

February 16, 1915

The town is full of people coming for Mardi Gras. We all dress in the colors of gold, green, and purple to celebrate. The colorful costumes, the jazz music, and the parades bring in endless men coming here on Basin Street for their further enjoyment. We take turns, with Madam Lucinda’s permission, to go out and celebrate. The mask covers our identities, so we are free to roam the streets, but we must still be careful. Our time out is short since there is much work to do at home.

February 28, 1915

{illegible entry}

March 1, 1915

Mr. Rivers came for a visit today. He had been out of town visiting relatives and taking care of his work. He told me once he was a banker, where I do not know or ask. He asked me if I had been writing in my journal, and I answered yes, when I found the occasion. He did not ask to read it, but instead, he asked me to read more poetry. The book is new, and I can smell the fresh ink. The spine cracks as I open it. It is a collection of many authors. He chose a poem by Anne Bradstreet:

Flesh and The Spirit

“In secret place where once I stood

Close by the Banks of Lacrim flood,

I heard two sisters reason on

Things that are past and things to come.

One Flesh was call’d, who had her eye

On worldly wealth and vanity;

The other Spirit, who did rear

Her thoughts unto a higher sphere.

“Sister,” quoth Flesh, “what liv’st thou on

Nothing but Meditation?

Doth Contemplation feed thee so

Regardlessly to let earth go?

Can Speculation satisfy

Notion without Reality?

Dost dream of things beyond the Moon

And dost thou hope to dwell there soon?

Hast treasures there laid up in store

That all in th’ world thou count’st but poor?

Art fancy-sick or turn’d a Sot

To catch at shadows which are not?

Come, come. I’ll show unto thy sense,

Industry hath its recompense.

What canst desire, but thou maist see

True substance in variety?

Dost honour like? Acquire the same,

As some to their immortal fame;

And trophies to thy name erect

Which wearing time shall ne’er deject.

For riches dost thou long full sore?

Behold enough of precious store.

Earth hath more silver, pearls, and gold

Than eyes can see or hands can hold.

Affects thou pleasure? Take thy fill.

Earth hath enough of what you will.

Then let not go what thou maist find

For things unknown only in mind.”The poem reminds me of myself. Good and evil competing with each other. Selling my flesh, does it take my soul? Does my reason, the sake of living and for my family, save it?

Mr. Rivers stayed the night and held me close to him. He makes me feel human, like all women should feel, not like property. He left the book of poetry with me along with a five-dollar gold piece.

March 23, 1915

I received a letter from momma today. She said the family is doing well, thanks to me. The paper smells of smoke from the woodstove and makes me lonesome to see momma’s face. To hear her voice. She can’t visit me, nor can I visit her, so all we have of each other is our letters. I remember the day we left North Carolina to come to Louisiana. We had family here, my stepfather’s brother and his wife. Here, the sugar cane was coming in faster than folks could harvest it. We were barely getting by sharecropping when my stepfather said we should move to where there was work. It was only three months till he worked himself to death in those fields, leaving us alone. It wasn’t long after I moved here to Storyville.

In Storyville, prostitution is legal. There are thirty-eight blocks that I can roam, shop, and call home. Outside of these thirty-eight blocks, I take a chance on being recognized and arrested. That is why I can’t visit momma, and it is too hard for her to travel to see me. Besides, I do not wish for her to see me here.

March 29, 1915

Victoria! Victoria! I cannot even write the words. My heart is heavy, and my eyes are blinded from my tears.

April 13, 1915

I will try to write about poor dear Victoria. She was a plump girl, short in height and large breasted. Her skin was the color of almonds, and her eyes sparkled when she smiled. She always had a kind word for everyone. She had been employed for about a year before I came. She had lived in a home for orphans until she came of legal age and having no skills and no family, she sought out Madam Lucinda for work.

My heart hurts as I write this to think of the injustices of life and death.

Victoria became pregnant, a hazard of her career. She informed Madam Lucinda, who then sent for the doctor to come and take care of the problem. Dr. Williams was out of town on holiday, therefore his stand in was called upon. The substitute arrived late in the night wearing rumpled, dirty clothes. He reeked of liquor, and his hands trembled. As he removed the tiny baby from Victoria’s womb, she screamed in pain and agony. There was nothing we could do. Finally, the laudanum took effect, and she managed to sleep through the rest of the night. The next morning the wails from her room were horrifying. She was burning with fever. The doctor was sent for once again, arriving too late except to see her lying there dead, as pale as the top of the sheets in which she lay. The bottom of the bed covers lay covered in bright, crimson blood. She was buried by noon in a pauper’s grave with no marking save a small homemade cross. Does God forgive whores? I pray he does.

I write to my mother, but I keep these terrors from her.

April 24, 1915

Another tragedy has hit us. Last night, we awoke to smoke coming from the downstairs parlor. It seems a client, Mr. Easton, confused from drink, wandered downstairs in the night and lit a cigar. He then fell asleep, setting the sofa ablaze and filling the house with thick, black smoke. The damage was minimal to the parlor. However, Mr. Easton did not fair as well. The police came, and we have been forced to close for an investigation. Madam Lucinda assures us that it will be brief as she has spoken to the police chief as well as the mayor. It does not hurt that they both frequent our home for their pleasures.

April 26, 1915

Men have come to clean and restore the parlor. Thickly piled carpets arrived along with new furnishings. The stench of burning flesh will take longer to leave our memories. No one goes to Mr. Easton’s funeral, it would not be proper, and since a story had been invented for Mrs. Easton and the public, any presences from this house would raise questions.

The paper read that Mr. Easton ran into a burning building to save a woman and child trapped within, and therefore he died a hero. He, of course, was nowhere near Storyville.

May 7, 1915

A German U-boat torpedoed the British steamship Lusitania, killing 1,128 people including 128 Americans. We all gather around the radio to listen, wondering if the United States will join in the war. It seems like many people want President Wilson to fight the Germans. Here, I fight my own battles.

May 17, 1915

I received a letter from my brother. Mother is not well though he says she will recover, and I should not come. Mother has fallen and broken her leg while working. He asked if I could send extra money that is needed for the doctor’s attendance. My sisters are taking her place at home as well as in the fields, which means they did not finish out the school year. They will be behind when the next year begins. My brother has taken a new job cleaning at the local university. He says it is good pay for a negro, but it leaves him little time for family matters. He has registered for classes there in the fall, and since he is an employee, he can attend part-time for free. The books, however, he will have to pay for from his earnings. I feel excitement for him, but I am troubled that I cannot be there for Mother.

May 20,1915

{illegible entry}

June 2, 1915

I cry for you my mother

As I know you shed tears for me

Our lives forever in chains because of our skin color

Will the world ever look into our hearts, our souls, and see?

June 14, 1915

Yesterday was a big day here on Basin Street. It was Madam Lucinda’s birthday. She will not tell us how old she is, and we dare not guess, at least in front of her! There was a grand party in her honor last night. Unimaginable amounts of food beautifully arranged and spread about on every table. Champagne for all! The band played delightful jazz music, and we danced. I felt like a princess. I had the good fortune of spending the evening with Mr. Rivers. His attention to me only enlarges my feeling of enchantment tonight. He holds me close when we dance, and I pretend we are in love with each other. I take in his scent, the exquisiteness of his eyes and the firmness of his shoulders. I secretly dream of our wedding day and our children that will never be. There is no poetry reading. Only a passion that is genuine, if only for the night.

I used to dream of having children but seeing my mothers’ struggles has made me change my mind. My children would still be called nigger. I couldn’t bear the thought of my daughter selling her body to live. I am careful, or as careful as I can be.

July 4, 1915

There was a block party and parade today to celebrate the holiday, Independence Day. Everything and everyone donning red, white and blue. As for myself and the rest of the girls, we did not get to attend. With all the out of town visitors, we were very busy. Hardly time to bathe between the men. The money and tips were good, although the day left us all exhausted. The heat, which is already unbearable, doesn’t help. In New Orleans, the summers are long, hot, and cruel.

July 25, 1915

I received a letter from my mother. She is doing better although she said she is walking with a cane. My sister Sally, the third born, is married and expecting a baby. There is a part of me that is happy for her, a life that I can only dream of, yet, I also worry. She married a negro sharecropper; she will struggle as my mother has.

Mother thanked me for the money and told me she had paid all the bills for her broken leg. She tells me she is sorry for the work I must do to help her. She says she prays for me.

She writes of another lynching close to her; a William Mitchell lynched in Sardis, Mississippi. She doesn’t say why, but I know it doesn’t take much. There is so much senseless hate in the world. I pray for my family.

August 20,1915

{Partial entry}

…she screams in the night, which awakens us all. We find empty bottles hidden in her bureau and underneath her bed. I am fearful she will have to be committed to a sanitarium…

September 14, 1915

My life here is not entirely bad. All the women have become like sisters to me, Madam Lucinda like a mother. We love each other and are a family.

There are other assets, as well. I have my own bathroom with both hot and cold water in which I bathe frequently. There is always plenty to eat, and I am never cold, although there is not much to be done about the heat in the summertime. When we are not busy, we gather around the parlor and play cards while we tell stories of our past. There is a commonness in our stories; We are all here because of need. We sell our bodies to live and to sustain those we love. Try as we may, it is difficult to hold ourselves in high esteem. Through our knowledge and stories, we can claim some of our dignity.

Ana is one of my closest friends here. She is from Georgia. She is darker-skinned than I am, tall, slim, and exotic in looks. She moved here for work when there was none to be found in Georgia, and she had to sell her baby to feed herself. Three men cornered her in a barn where they violated her and beat her within inches of her life. She has a mark above her right eye, and her heart carries many scars, as proof of the torture she endured. She says she had no feelings of love or attachment to the child since it was conceived during a brutal rape. I see the look in her eyes when she talks about the child, and I don’t believe her.

Then there is Olivia, a woman of about thirty with the voice of an angel. She is from Virginia and never talks much about her past. Her face matches her beautiful voice, and her smile lights the room when she walks in. She doesn’t have much education, but she has an abundant amount of common sense. She and I have stayed up till the early hours of the morning just watching the stars from the rooftop.

The hour is late, and I must sleep.

October 4, 1915

{illegible entry}

October 29, 1915

{partial entry}

Leaves of crimson, orange and gold fall silently to the ground

I see the beauty in death

Stars fill the night sky, and I watch as one falls

I see the beauty in death

November 5, 1915

A letter from mother bringing bad news has arrived. My sister Sally has died while giving birth to her baby boy. Mother said the baby tried to come into the world feet first and Sally lost so much blood that she couldn’t hold out. The baby was named Zeke and is buried in Sally’s arms.

I long to be home with momma, especially now that she is grieving. I know my presence would not replace Sally, but maybe seeing me would give her strength.

The envelope included a letter from my brother Thomas. He writes he is doing well and is continuing both his work and his classes. He says he wants to be a doctor. I know my brother, and he will succeed.

Neither mentions my youngest sister, Bell, in their letters.

November 15,1915

{illegible entry}

December 23, 1915

Olivia has died from syphilis. She was hospitalized a week ago. She had been fatigued and seemed to become thinner, but she stated she was just simply tired when we inquired. Madam Lucinda, when she noticed, wasted no time in sending for the doctor. Olivia, at this point, was covered in sores and developed a high fever. There was little hope for her.

Disease is a fear that we all share mutually here in Storyville. This risk is faced daily and would be an end to our livelihood and possibly our lives. Is there any place to go from Basin Street, except the grave?

January 3, 1916

I am going home! Mother has written informing me that she has found employment for me as a housemaid in a new hotel that has been built near the university. I would gladly go back to sharecropping to be near my family, but I am grateful for the job at the hotel. Madam Lucinda and the girls say my leaving will be bittersweet. They are happy for my chance at a new life, but they will miss me. I will miss them as well.

January 12, 1916

As I am preparing to leave, I have one last visitor, Mr. Rivers. He brought me a new journal and encouraged me to keep writing. He graciously walked me to the train station, and before we parted, he kissed me gently on the cheek.

Works Cited

“’Song of Myself’: A Poem by Walt Whitman.” Interesting Literature, 4 Nov. 2018, https://interestingliterature.com/2018/11/06/song-of-myself-a-poem-by-walt-whitman/.

Hickman, Kennedy. “America Joins the Fight in World War I.” ThoughtCo, ThoughtCo, 29 July 2019, https://www.thoughtco.com/america-joins-the-fight-in-1917-2361562.

Jani, Brian. “Flesh And The Spirit, The.” PoemHunter.com, 31 Dec. 2002, https://www.poemhunter.com/poem/flesh-and-the-spirit-the/.

“Judith.” Poem: Judith by Eloise Bibb, https://www.poetrynook.com/poem/judith-4.

“New Orleans Temperatures: Averages by Month.” New Orleans LA Average Temperatures by Month – Current Results, https://www.currentresults.com/Weather/Louisiana/Places/new-orleans-temperatures-by-month-average.php.

Storyvilledistrictnola.com, http://www.storyvilledistrictnola.com/farewell_storyville.html.

Sep 9th, 2019 by felton21

Dorian always gets antsy when it rains. Panics when the water gets above the soles of his shoes. Always fights to get to the highest point at the first flash of lightning or roll of thunder. He doesn’t like storms, or rain, or dark skies, or clouds. No one can blame him, though no one understands him. Storms can’t hurt him anymore. They haven’t been able to for fourteen years.

Shiv knows it’s PTSD from Katrina and he knows Dorian isn’t the only one who feels it. They only pick on him because he shows it outwardly. A lot of people in this graveyard ended up here because of Katrina, though they play off their own hesitation of storms by picking on Dorian’s. They’ve managed to convince themselves that being scared is ridiculous since they’re dead. Nothing can hurt them anymore, so why is Dorian so scared?

Shiv can see through their taunting, though. He sees the way they eye the sky whenever an unexpected cloud covers the sun. He watches the way they watch the sewers and storm drains get rid of the rainwater and how their (metaphorical) breaths hitch whenever it draining start to slow. He watches but doesn’t voice his observations whenever the teasing starts. He knows they all have their own coping mechanisms. Besides, Dorian allows it. He, too, knows they need their releases and he doesn’t mind them letting it out on him. He can handle it.

The rain is heavier than usual tonight and Dorian is on his usual perch, straddling the highest cross in the yard as he watches the streets beyond the fences. There’s no flooding yet, but the drains aren’t pulling water as fast as it should be. An inch of water already sloshes underneath the tires of passing cars and bumps against the sidewalk in front of the graveyard. A few of the older residents of the yard cautiously hover around the gates, cracking jokes and trying to keep the air light as they watch the steady rain add to the pools on the streets.

“There’s no place to evacuate here,” Anita, another Katrina victim, had whispered to Harvey a few months ago. Shiv had almost felt bad when he eavesdropped behind a tomb a few yards away. He’s always been a nosy person and yes he has a limit of what he’ll listen to, but he hadn’t realized how personal things were giving until it was too late. “How will we get the kids out? What if—”

Sep 9th, 2019 by bell20

509 South Main Street, Blackstone, Virginia. 23824.

I don’t remember what the kitchen looked like, other than the tacky black and white linoleum on the floor. I remember that the dining-room was where my mother kept the hundred-gallon fish tank and that I had one of those bottom-feeding eel things that I named Jojo. I was fascinated by that tank; the lights, the fake coral that all of the fish would swim through. I remember standing on my knees to peer in when everyone else had gone to bed, when the rest of the house was dark and it was just me, the lights, the fish, the water.

My room was on the second floor, just to the left of the top of the staircase and my bed was in the corner, beneath the window whose frame was painted khaki, like the rest of the trim in that house. It was lead paint. I liked to chip it off when my mother made me angry, or write on the flakes in Sharpie marker and hide them under my curtains. There was a walk-in closet at the end of the room, where my dresser and glass vanity table were. It’s strange to think of that room now, the bedroom of the house I grew up in where I spent most of those angsty pre-teen years and had friends over for the first time, and realize that I don’t remember much about it other than the furniture and the time I found a pair of glasses that I’d been missing for several years behind the radiator.

I think of these rooms when I pass that house by now, the one my parents call the brown house, as an adult that has lived in several different houses on opposite ends of the country. I think of all the Halloweens and the days beforehand that our family spent carving ten or twelve pumpkins to line the front sidewalk; I remember the Christmas mornings when my brothers and I would stampede through the house to wake our parents so that we could open presents and how the wrapping paper drifted through the air like false snow, the sound the torn pieces made when we kicked them like soccer balls just to watch them jerk in different directions and fall back to the floor; I think of my parents room and how large it seemed compared to the rest of the house, how their bedroom furniture seemed to float in the middle of the room. But mostly I remember the foyer.

There was a small square of linoleum on the floor, just inside the front door. The pattern reminded me of a giraffe’s, but instead of yellow and brown, the spots were dark green and the rest of it was beige. The surrounding floor was covered in carpet that was an awful shade of pink. In my memories, it is the color of Pepto-Bismol.

Nearly every wall in that house was covered with brown paneling; the cheap kind, the sort that would snap back against the wall behind it if you pulled it down. There were dark brown grooves between each panel, so dark they almost looked black, but those details aren’t important. What I remember most about that room is the chandelier and the matching table and mirror that my mother bought to sit beneath it.

When we moved into the brown house, I remember that I felt like a princess because it was so much more than the house we’d lived in before—but I’ll get to that later. This one was bigger; I had a bigger room, a bigger yard, and a chandelier on top of it all. It was a terribly tacky thing, with metal arms that were wrapped in a cheap gold foil and glass crystals that hung in all directions. But when my mother bought that table—a half-circle, made to stand against the wall, with four legs and a shelf underneath, maybe a foot off the floor, and a big, oval mirror made of matching wood—the light that came from the chandelier reflected on the glass, and it made the paneling on the other side of the room look as if there were rainbows hidden in the grain. The grooves between the boards changed from the dull dark brown into the bark on a tree, with highlights and low lights and texture. All of the brown and the ugly and the cheap came together when the lights turned on and made something small, something beautiful.

When the older of my brothers started to crawl, he would situate his body in front of the table, and back in so that his legs were beneath the shelf. When no one noticed his triumph, he would start to cry until we cheered him on.

148 Winesap Road, Madison Heights, Virginia. 24572

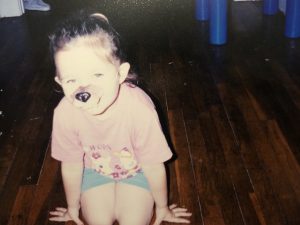

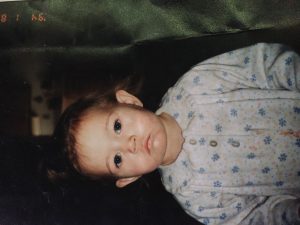

When I was younger I didn’t understand the fascination with baby pictures. I thought they were overrated—why would anyone want to look at the baby when they could look at the adult?—and just another way for grown-ups to tell me about all of the things I didn’t know. I was a smart kid; I made good grades, I asked a lot of questions, I read the encyclopedia for fun—what were they doing telling me all the things I still had to learn? I suppose I thought learning ended after high-school.

I think I realized how ridiculous that all was when I was about to graduate high school, when I realized, oh, shit, I have to like, be an adult now and learn how to balance a checkbook and pay taxes. It felt like I’d been waiting so long for those four years to end that I hadn’t realized what was beginning. But the moment that happened, the second that I realized I was about to become a different person, was the moment I realized that something similar had already happened to me.

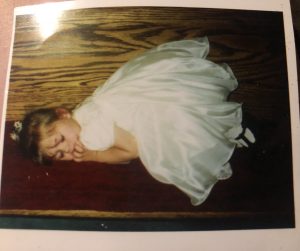

I had to find a baby picture to use to go along with my drape photo for the senior quotes in the yearbook. My mom keeps all of our baby pictures in a wooden chest that her grandfather built for her before I was born, and it’s a pain in the ass to dig through. But she sat with me and helped me look. We ended up choosing an old Polaroid from my parents’ wedding day.

I was two years old when they got married, and so naturally, I was the flower girl. My dress was white with a big tulle skirt and I wore white tights that my mom says I hated and little black flats. There was a bow in my hair. But the picture is of me asleep in a church pue, my tiny hand and fingers in my mouth. I think every person in my family has at least two copies of that picture. My mom cooed and teared up but I remember feeling sad. Looking at that girl, I could see the similarities between us—our hair falls from where it’s been put up in all the same places, and our noses and mouths are shaped the same way—but it felt like looking at someone I didn’t know, or maybe someone that died. I look at that picture now and realize that I have no memories of that day. I don’t know that little girl, what she wanted or dreamed of, what her favorite food was. I know she loved The Little Mermaid, and that by that point she could sing the entire soundtrack. But I don’t know her because she doesn’t really exist anymore; she stopped existing the moment that flash went off, the moment she woke up and went back to dancing and blowing bubbles and being passed from person to person.

Disconnect.

707 Nottoway Avenue, Blackstone, Virginia. 23824.

My grandparents’ house is a place that I am not fond of. It sits on the edge of one of the lower-income neighborhoods (though that isn’t the reason I’m not fond of it), and it used to be blue. My family has a thing, I think, for odd colored houses. I remember telling my pre-k and kindergarten teachers, when I rode the bus there after school, that their house was blue. I was very excited about that.

Despite the ways in which I hated there, and still do because my grandfather is a miserable man who enjoys making those around him just as unhappy, it was where my parents and I went when it snowed. As a child, I had an irrational fear of the snow: I knew what the ground looked like beneath it, and I could see the driveways and roads where it had been cleared, but I was terrified that as soon as my foot fell through the soft, cold blanket of white I would go under, slip into depths of icy water, and I did not know how to swim. My mother would wrap me up in layers of long-johns, sweats, socks and coats and boots, but as soon as she moved to set me down on the smooth surface of the snow, I remember feeling like I could hear the ice (that I knew wasn’t there), cracking. Like I could see deep blue water behind my eyelids. I was terrified.

So my mother would set me on one of the wrought iron benches that my nana had arranged in the yard, just off to the side of the front porch. I have a picture, taken from that porch, by my nana or my grandfather, I’m not sure, but I am sitting, or maybe standing, right on or next to that bench, looking down at the fluffy white ground in wonder. I don’t remember what I was thinking, but I remember, years later, standing in our driveway, when my family relocated to Washington state, waiting for the school bus with snow nearly up to my knees, and thinking about how afraid I was of the snow as a little girl.

There was no humidity there, but the wind was so cold that it chapped my lips. The snow was heavier, but less wet somehow, less depressing. Even though it was different, it reminded me of where I came from: that tiny yard, across the street from the preacher’s house, where my nana was waiting inside with a cup of cocoa and thick wool socks to put on my feet when I was carried in. I remember, waiting at the end of that driveway, how I wished that I’d been right about the snow. How I wished that there was some secret body of water beneath it to splash up around my ankles and drag me under, back to where I came from, even though it hadn’t been perfect. I look at that photograph and think of how comfortable I was in my discomfort at being in their yard, in their house. How easy it was to be there, as compared to a state three thousand miles away, standing at the end of a driveway waiting to go to a place full of people I didn’t know and didn’t want to get to know.

How strange. The baby version of myself was the blueprint for the self I am now. I knew this. It’s logical: we are born with natural dispositions and genetic make-up and likes and dislikes. But it doesn’t feel like that little girl standing at the end of a bench was ever a part of the woman I am now. The year I spent in Washington was miserable, I admit, but it taught me a lot about the ways in which people differ from place to place, and how growing up in one place can make you more resistant to another. I didn’t want to like it on the West coast because I ached for what I was missing on the East. Now that I am older, I wish I’d paid more attention to the landscape, that I’d been more open to the way of life that existed there and the traditions that my friends, members of the Spokane Indian Reservation, upheld.

5060 Highway 29 South, Hunters, Washington. 99137.

It was a yellow house. Split-level. The night we got there, after a week of driving across the country and seeing mountains for the first time – and I mean real mountains, the kind that make you think about how inconsequential and tiny you are as a human, not the hills of the East coast – I got out of my mom’s Chrysler Town and Country minivan and thought, We traveled three thousand miles for this? It was dark out but there was a lamp post in the back-yard so the structure was back lit and the pale yellow color of the day time was made to look orange against the darkest sky I’d ever seen.

Hunters, Washington is about two hours North of Spokane, both of which are on the Eastern side of the state. The estimated population is little more than 300. It’s really more of a street than a town, consisting of a convenience store that has things like Ibuprofen and bread and milk. Other than that there’s a post office, a bar, and a diner where the old men go for their daily morning dose of shitty black coffee and middle aged waitresses that have sons in the local high-school who play football. Of all the things I found in that town that felt familiar, that tiny little restaurant was the most striking.

Our time in Washington was before I made it to high-school, so it was before I started working in the local Blackstone restaurant where my mother had worked when she was a teenager. But years later, when we’d relocated back to Virginia, and I spent my Saturday and Sunday mornings in Blackstone waiting on a table of old men (that had been nicknamed the “Big Boys” years before), I’d think of that restaurant, and the ways people can be different from place to place, but the ways in which you can also count on old, cranky white men to seek out the best place to go to get bad coffee and average service. I came to love those old men, in a weird cranky-and-distant-but-still-all-together-affectionate way, but that’s besides the point.

The night I got out of the minivan and looked at the house I’d be living in for the next year (although I didn’t know it would only be a year at that time), I remember glancing up at the sky and noticing how different the stars were. They were brighter, more vivid, and it felt like they were winking at me in cruel humor, as if they were saying, “Welcome to planet Washington, where the people are unlike any that you’ve encountered before, and nobody drinks sweet tea!” And then we went inside.